For Rev. John Perkins, his life and ministry have focused on reconciliation

Editor’s note: This piece on the Rev. John Perkins, his years in ministry and his essay on living the truth in a polarized society were originally published on the former Overby Center website in August of 2023. It is republished here with appropriate updates.

By Will Norton

Rev. John Perkins celebrates his 90th birthday in 2020. Photo courtesy of John Perkins’ family.

The Rev. John Perkins was born near New Hebron, Miss., and grew up with a strong grandmother.

After they married, he and Vera Mae moved to Los Angeles and, over time began to work with Child Evangelism, an organization of volunteers who present Bible accounts to children in ways they can understand.

In 1960 he and Vera Mae returned to Mississippi and presented Child Evangelism programs in public schools. His programs were extremely popular, and he attracted attention for his effective communication skills.

Rev. John Perkins revisits a place of his youth in New Hebron, Miss., in 2016. Photo courtesy of John Perkins’ family.

He developed the Voice of Calvary ministry in Mendenhall that realized the economic needs of his people. As part of that ministry, he organized more than 25 economic cooperatives for Black people in Mississippi. Vera Mae ran a day-care center, and they supported voter registration. In 1967 they enrolled their son in the all-white Mendenhall High School.

These previous efforts led to his arrest two nights before Christmas in 1969. He and Doug Hummer, a 22-year-old white worker at Voice of Calvary, went to the grocery store in Mendenhall and saw a young Black man having trouble cashing a check.

The young man had been drinking, and Perkins asked him to go home with him. Unfortunately, the owner of the store had already called the police, and the squad car arrived as they were getting into the car. The police saw the young man with Perkins and followed them across the railroad tracks, down the dirt road in the Black section town.

When they were a few blocks from Voice of Calvary, and the Perkins residence, the policeman turned on his red light. Hummer got out first and asked why they had been stopped.

“You just shut up,” the policeman said. “Stand aside.”

When the young Black man got out of the car, the policeman said, “You’re under arrest for public drunkenness.”

“Public drunkenness,” Perkins said. “Wasn’t he in the car with us?”

“You shut up, Perkins,” the policeman said.

Perkins left, walking home, and Hummer brought the car home a few minutes later. Perkins went to the young man’s home and told his mother what had happened. Then he came back to the church.

Young people were rehearsing a Christmas program, and a young woman told John about another young man who had been dragged out of a nearby Black church earlier that day. He had been taken to jail and beaten.

When Perkins told her what had just happened, she said, “They’re going to beat him, too.”

Other young people gathered around the conversation with Perkins, and they wanted to go to the jail to see the boy.

“We heard you’d beat him up,” one of them said.

“We haven’t laid hands on him,” the chief said. “Go in and see.”

So, they did.

And the man locked them all in the cell. When the sheriff and the highway patrol learned that some young people had been locked up for asking a question, the police tried to get them to leave. But the young people wanted to know why they had been locked up. Finally, the police removed the young people and charged Perkins with disturbing the peace.

Perkins and Hummer spent the night in the Mendenhall jail, but the young people had worked all night fixing signs. They were determined to boycott the town until Perkins and Hummer were released from jail. At 10 a.m. the next morning, the police came to Perkins jail cell to take him to trial.

Perkins realized they were feeling pressure. It was just before Christmas, and the protesters were causing others to be off the streets.

“I can’t have a trial without a lawyer,” he said. Perkins’ lawyer told him to stay there. “Make ‘em sweat. Christmas Eve—just before nightfall—make bail then.”

Perkins followed his lawyer’s advice, and the protest grew until he was released.

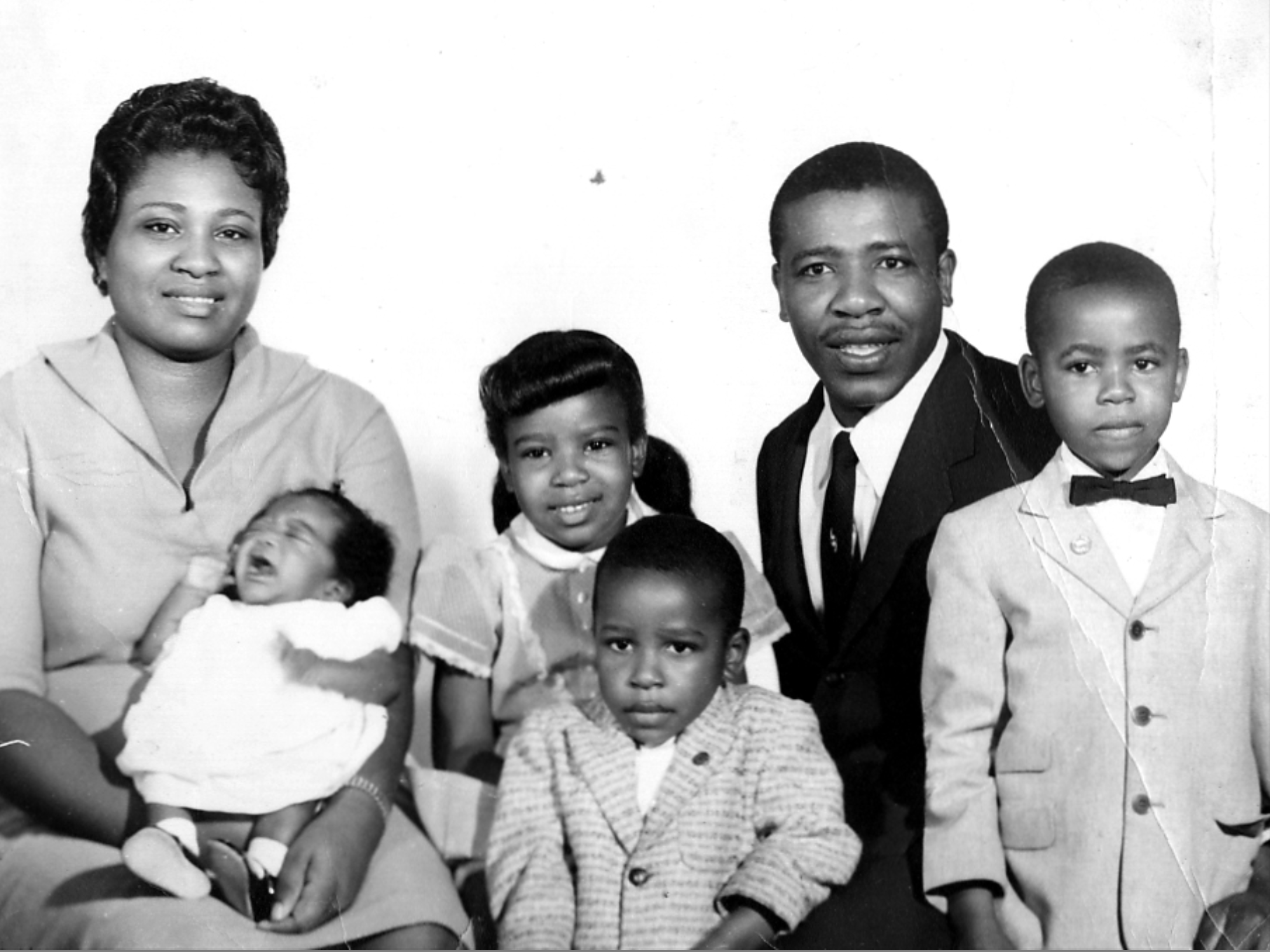

Rev. John Perkins and wife Vera Mae with children in a family photo in 1959. Photo courtesy of John Perkins’ family.

The Brandon Jail

I was managing editor at Christian Life Magazine in 1969 and had been told about Perkins by a missionary doctor who was touring the U.S. to learn what evangelicals were doing about segregation and human rights. “He’s a Bible-believing minister,” the missionary said.

I was taken aback. At that time evangelicals claimed that they should not be involved in civil rights because religion was to be separate from government and politics. So, what this young minister was doing was radically different from most evangelicals.

A few weeks after that conversation with the missionary doctor, I flew into Jackson. John and Vera Mae met me at the airport, and we drove to Mendenhall for several days. That’s when I learned about the incident in the Brandon jail.

Several weeks after the arrest in Mendenhall, Hummer was chauffeuring a van full of Tougaloo College students back to school after participating in a community-organized event. A highway patrolman pulled him over, ordered him out of the van and instructed him to sit in the patrol car.

By that time, more highway patrolmen had arrived and ordered the students out of the van. Then they took Hummer and the students to the Brandon jail. One other van load did not get stopped. The driver called Perkins with news about the incident, and he and the Rev. Currie Brown set out to make bond for the students and Hummer.

“Just innocent fools, we were,” Perkins told me. “They set us up. When we got there, we told one of the marshals standing outside that we’d like to see the sheriff.”

The marshal went to get the sheriff but, “Instead of the sheriff coming to see us, about 12 highway patrol came out and arrested Cur and myself and took us into jail. They almost beat us to death.

“They began to crack me over the head and to say that this was that smart nigger. And they began to just beat me and beat me and beat me. The floor was smeared with our blood. Meantime they got a call over the radio that the FBI was coming, and so they had me mop all of the blood. And when I got through mopping the blood, they had me go into the back room and wash my head. But the FBI didn’t come, and they took my picture and fingerprinted me, and this was when they really beat me.”

Perkins told me the story as he sat in his office late one night during my visit in June 1970. He spoke calmly. He didn’t seem angry. He showed no hate, no hostility.

“When they were taking my fingerprints, one of them took a pistol, put it to my head and pulled the trigger. They were like savages – like some horror out of the night. One time they took a fork and bent the two middle prongs down and pushed the other two up my nose until the blood came out.

“You get upset,” he said. “It’s the momentum of the thing. The highway patrol is there with themselves as God. They can do what they please. We’re really at their mercy. I know man is bad … depraved. There’s something built into him that makes him want to be superior. If the Black man had the advantage, he’d be just as bad. So, I can’t hate the white man. It’s a spiritual problem – Black or white.”

Later Perkins and I visited the office of the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law. I saw photos of Perkins with his eyes swollen nearly shut and bruises all over his head.

“I don’t tell many people what happened because I wouldn’t expect them to believe it,” Perkins said. “I wouldn’t expect good Americans to believe how the police and highway patrol had that thing planned and how those people acted.

“Most white Christians don’t want to believe this. They close their eyes to it. Because if a white person minds his own business, he goes up the ladder. He doesn’t get in trouble. So, they figure that a black guy who gets in trouble isn’t obeying the law. And the press plays up this protest thing so much that it sounds like some more people just trying to get away with something.

“America has the power and the mechanics to do the job, if it will face the problem,” he said. “I don’t believe our leaders should listen just to the noisy guys. They would not be leaders if they did. I believe that Black and white Christians will be able to deal with today’s problems.”

Through the years he often has talked about the influence of his grandmother. She helped him understand that he was equal to white people, and he has used that understanding and his faith to teach young men and women to accept others, to not be self-righteous and to love and work with others for reconciliation.

—————————————————————————

Will Norton is senior fellow emeritus at the Overby Center for Southern Journalism and Politics, dean emeritus at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and former dean of the School of Journalism and New Media at the University of Mississippi.

Trying to live the truth in a polarized society

(The Rev. John Perkins, a Bible teacher, author and community developer, celebrated his 95th birthday last June in West Jackson. He has been awarded 17 honorary doctorate degrees; has served on many boards, including Word Vision and Prison Fellowship; served on or advised the presidential task forces of five U.S. presidents; and is the author of 17 books. He has spoken in many places around the globe and is co-founder of the Christian Community Development Association. On October 3 and 4, 2025, John and Vera Mae Perkins celebrated 65 years of justice, leadership, and transformation through the work of the John & Vera Mae Perkins Foundation. The event was at the Terry Woodard Ballroom of the Student Center at Jackson State University. The Rev. Dr. Derwin Gray, former NFL standout with the Indianapolis Colts and the Carolina Panthers, was the keynote speaker for the evening. Dr. Gray and Vicki Gray are the co-founders of Transformation Church, in Indian Land, S.C., just outside of Charlotte, N.C. He serves as lead pastor and she serves as executive director of spiritual formation and staff health.)

By Rev. John Perkins

Vera Mae and I have had an exceptional life. It’s been a life of personal and professional challenges and uncommon fulfillment.

I was fortunate that a young writer was told about me and came to Mississippi in June 1970 and wrote articles for several magazines, and I was invited to tell my story and become friends with leaders here and in other nations.

Yet, as I look back over the years in which I have remembered my creator, I am a broken man because I realize how much I have come short of the glory of God.

I have come to realize that I have to stop defining who I think the other person is.

I have to respect the other person.

I have to love that person.

I have to forgive that person.

I have to work with that person.

Today, our society seems to have made a major turn. However, if we keep focusing on past prejudice and do not forgive, we will not make the most of this moment. Without reconciliation, racism continues, and there is no reconciliation without forgiveness.

The issue that we call race is really a human problem. It began in the Garden of Eden and we have color coded it. We have done exactly what Adam and Eve did. They blamed others for their wrongdoing.

The challenge today is to see the wrong in ourselves and to forgive others and draw them to us so that we will be gracious and forgiving people and emulated by others.

There is wrong everywhere, but the wrongs will not be corrected if we do not recognize our own prejudices and quit branding others as bigots and fail to forgive.

My approach needs to be one of acceptance.

Arguing with a person about his or her views is not going to get us anywhere. Listening to them and showing them love and forgiveness is the only way others are going to learn to accept those with whom they disagree.

When I jump to let someone know that they are not correct, do you really think that is going to help them be more accepting?

Early in my ministry, I did not have the strength in some very important situations to try to find the common ground with others so that they could see in my life what I believe. As a result, they found it difficult to accept me. Instead, I tried to use power to cause them to deal with me. My comments and my tactics estranged them.

Now I may be seeing the world through old and outdated eyes, but I am convinced that thinking I am right and pressuring others to do what I want them to do is to follow the example of the Pharisees, the enemies of Jesus.

My perspective cannot be self-righteous.

Putting my political views ahead of my love of Jesus and selling my politics instead of the Gospel is a form of self-righteousness. People of the Book know that we all are either Sons of Adam or Daughters of Eve. We are a fallen race.

If I were a white man with money in the early 1800s, I might have gone to the slave market and bought slaves. I might have thought it was okay because that was the only way I was going to make money and protect the possessions that God had allowed me to accumulate.

My actions need to be bathed in forgiveness.

I have known great injustice.

Early in life I experienced the evil of separate but equal.

I was not paid fair wages when I worked for others as a boy.

I saw my brother shot beside a theater, while he was waiting to see a movie.

I saw discriminatory practices in the stores of the community in which I lived.

Because of those experiences, I work to teach young men and women to accept others, to not be self-righteous and to love and work with others. The emphasis has to be on forgiveness.

There is a God who has forgiven me, a fallen human being and, while others may have had experiences that were not as discriminatory as those I experienced, I have to forgive them if I truly understand the meaning of forgiveness.

Today I confess that, despite the Lord’s allowing me to participate in what He has been doing concerning racial reconciliation, we seem to be in a more critical time than I can remember.

I do not see acceptance of others.

I do not see forgiveness.

I see self-righteousness.

I am broken.

I am searching my soul as to why reconciliation seems to be as much of an issue today as it was when I was a child, and I am renewing my commitment to not being a Pharisee who puts his politics and his perspectives on race before his love for the Lord.

My approach cannot be built on power. It must be about truth, the truth that Jesus lived in accepting those with whom He had differences. He forgave them and loved them.

I am broken because, despite my efforts, I know that I have come short of what the Lord intended for me to be.

Now in my last years, I pray that He will enable me to participate in a life that fulfills His will for me.